Orville Peck – the mysterious masked cowboy singer – has beguiled listeners with his queer, romantic take on Johnny Cash’s outlaw country music. He also channels Elvis Presley’s swoony rockabilly, Roy Orbison’s crooned psychedelia and kd lang’s cowpunk cabaret. But Peck sings openly of same-sex unions – desire, heartache and loneliness.

There’s been fervent speculation about this storyteller’s identity – ‘Orville Peck’ an alias. However, with his Sony EP Show Pony – a postlude to 2019’s debut album Pony – Peck, based in Canada, should finally transcend any novelty status. Besides, Show Pony includes his biggest pop moment: ‘Legends Never Die’, a duet with Canada’s Shania Twain, the Queen of Country Pop (premiering today at 2pm).

In recent years, country has undergone a rejuvenation, even revolution, with a wave of diverse acts challenging misconceptions that it’s a space for the reactionary straight cis white male. Simultaneously, creatives have resisted the form’s purism and notions of authenticity in a way not heard since a mirthful Tammy Wynette joined The KLF on their acid-house banger ‘Justified & Ancient (Stand By The JAMS)’. In late 2018, Lil Nas X went viral with his camp trap-country mega-hit ‘Old Town Road’, subsequently reworking it alongside Billy Ray Cyrus. The Atlantan was hailed as a modern gay Black country star – but his success prompted discussion about the historic erasure of Black artists from the country & western idiom.

That’s not to say that queer country is new– the cult Seattle band Lavender Country releasing a gay pride album in the ’70s. Later, another Canadian artist, kd lang, broke down barriers. She partnered Orbison on a rendition of ‘Crying’ before crossing over with her own Ingénue.

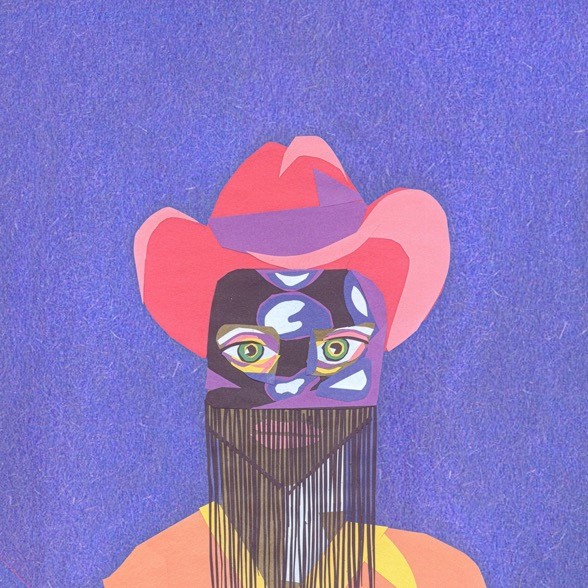

Known for concealing his face with a fringed Lone Ranger mask, Orville Peck has generated as much media curiosity in his costume and aesthetics as his music, being influenced by John Waters’ auteur kitsch and David Lynch’s American noir. Nevertheless, he’s divulged few biographical details in interviews. Peck has shared the rationale for his anonymity in a statement: self-care. “Traversing this industry as a gay country musician, I already endure daily hate, bullying, aggression and people actively trying to discredit what I do. So whether or not Orville was the name I was born with is irrelevant. I understand there is a temptation to try and unmask what I do, but to do so would be to miss the point entirely. All I ask is that people respect my work (and more importantly) my fans enough to maintain this crucial part of my expression as an artist.” In fact, his country does reveal emotional truths.

In early 2019, Peck delivered Pony on Seattle’s fabled grunge label Sub Pop, having first aired the yearning ‘Dead Of Night’ two years prior – a single accentuating his vocal pliability. The baritone refashioned classic country balladry while veering into Americana and post-punk – handling the LP’s production and a deal of the instrumentation himself. ‘Hope To Die’ evoked a shoegaze Chris Isaak. But, for all the theatricality, Pony felt raw – Peck crooning about past damaging relationships in the bare ‘Big Sky’. ‘Nothing Fades Like The Light’ was synced for HBO’s Watchmen.

Over summer, Peck toured Australia, appearing at the Sydney Festival. He guested on Diplo’s cannily curated country album, Chapter 1: Snake Oil, contributing the semi-spoken ‘Intro’. Unusually, Peck was billed to perform at both Coachella and its country spin-off Stagecoach Festival until the COVID-19 pandemic struck (he’ll support Harry Styles’ Harryween concerts at New York’s Madison Square Garden, rescheduled to 2021). In the interim, he announced Show Pony for June, only to delay it so as not to distract from the Black Lives Matter protests. Peck hyped his song with Shania Twain, a childhood idol, by posting a snap. To mark Pride, he issued a distinctive cover of Bronski Beat’s synth-pop ‘Smalltown Boy’ for Spotify.

Show Pony has materialised within weeks of Taylor Swift’s folklore – the country-pop megastar, rarely recognised for her formative disruption of Nashville conventions, pivoting to indie-folk. Peck, too, balances a personal need for catharsis with an instinct to archly self-mythologise. Indeed, he is no postmodernist fabulist, rendering his experiences figuratively rather than fabricating. Peck ironises and transgresses tropes in celebrating them – his favourite that of the cowboy rebel. Somehow, Peck’s work is expansively neo-traditionalist.

Show Pony‘s lead single, ‘Summertime’ is part-Billy Idol torch song; part-Ennio Morricone spaghetti western film score. A precariously nostalgic Peck sings about temporality, the momentum of hope, and imagining better days. Conversely, he conveys the world weariness of the outlaw (or outsider) on ‘No Glory In The West’ – quieter with acoustic guitar. Less stylised, ‘Drive Me, Crazy’ is a live-sounding barn number with rock guitar and piano. ‘Kids’ is reflectively wry.

Peck often covers country standards in gigs, teasing out sexual and gender nuances (kd lang did something similar for 1997’s Drag, ostensibly reinterpreting songs with a smoking theme, but really exploring social masquerade). Here, he presents a studio version of Bobbie Gentry’s 1969 hit ‘Fancy’. Gentry, a feminist country trailblazer, quit the music industry to supposedly become a recluse. Reba McEntire brashly revived ‘Fancy’ in the ’90s. Yet Peck’s ‘Fancy’ is Nick Cave-mode gothic.

Still, the buzz song on Show Pony is that duet with Twain. The ’90s phenom embarked on an extended hiatus in 2004 due to health concerns, eventually returning with a Las Vegas residency and a chart-topping confessional album, Now. That alone makes Peck’s collab a coup. And ‘Legends Never Die’ is a rhinestone-studded rodeo “bop” that deserves radio attention.

Peck is a wanderer and a wonderer. But, with Show Pony, he rides home.